Alright, so Keratoconus (KC).

You may or may not have heard of it, but let’s dissect the name a little.

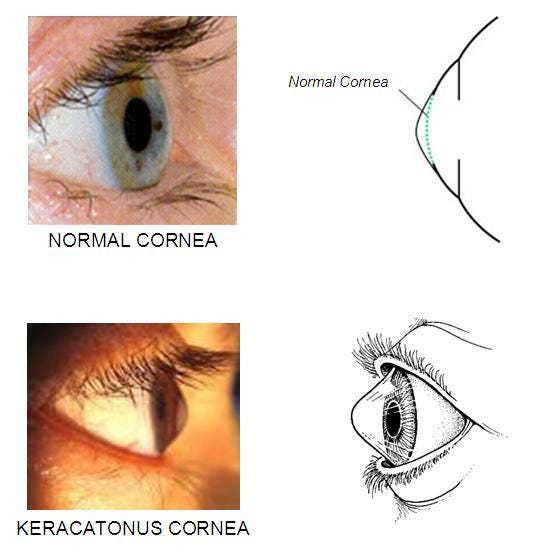

Kerat- or kerato-, refers to the cornea (the clear front part of your eye).

Conus, Latin for... you guessed it, cone.

Coning of the cornea.

And that’s our topic for today. So let’s get into it.

How does the cornea cone?

Well, the how is a little complex.

In short, the cornea gradually thins, loses its structure, and bulges into a cone-like shape.

The long answer? Research is still trying to piece it together.

What we do know is that under the microscope, keratoconus corneas show thinning, scarring, and breaks in the Bowman’s layer (one of the 5 layers in the cornea). Some research has shown that it could be due to imbalances in enzymes that break down collagen, making the cornea weaker over time.

You still with me?

There’s also evidence pointing to an inflammatory process.

Studies have found increased levels of inflammatory molecules (like MMP-9, IL-6, and TNF-α) even in early, mild cases of KC. But keratoconus doesn’t quite fit the profile of a typical inflammatory disease, making it a bit of an enigma.

Why does the cornea cone?

As for why, we don’t actually know for sure.

But it is described as being a multifactorial condition, meaning that many factors contribute to the why.

The greatest contributing factors appear to be genetic and environmental (we will talk about in a bit) factors. Around 1 in 10 people with keratoconus also have a parent with the condition.

Here’s why you should care

I’ve mentioned that genetic and environmental factors play a role in KC.

So —

if you have a parent with KC; you should care.

if you have conditions such as, retinitis pigmentosa, Down syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, hay fever and asthma; you should care

if you are AN EYE RUBBER and/or sleep with your HAND AGAINST your eye; you should care.

Majority of these factors that are genetic, you can’t control.

But the environmental ones, you can control.

Here’s why the Black and POC community should care

While KC affects all ethnicities, studies suggest that Black individuals are at higher risk of developing more severe forms of the disease.

Yet, KC remains underdiagnosed and undertreated in our communities.

A study by Nugent et al 2023 found that keratoconus presented more aggressively in Black patients at presentation compared to White patients. Papaliʼi-Curtin 2019 reported a higher prevalence of KC among the Māori population.

Several other studies (Kok et al 2012, Pearson et al 2000, and Georgiou et al 2004) have shown that Asians (particularly Indian, Pakistani, and those of Middle Eastern descent) not only have a 4x increase in incidence compared to their white counterparts, but also had an earlier onset of the disease.

Okay, but why? 👀

Good question.

The simple yet complex answer is socioeconomic disparities.

Truth is — non-White patients, especially those with lower income and government-funded insurance, are more likely to present with severe keratoconus and experience delays in receiving treatment. And when they do receive treatment, it’s more likely to be the more invasive cornea transplant rather than the fancy less invasive option, corneal cross-linking.

How do I know if my cornea is coning?

Symptoms of keratoconus may change over time but they include:

Blurred or distorted vision that worsens over time.

Heightened sensitivity to bright lights and glare, particularly at night.

Sudden deterioration or clouding of vision.

Frequent changes in prescription glasses without clear improvement.

Takeaway this

Get checked early:

The earlier keratoconus is detected, the better the outcomes especially if you are someone that is at-risk individuals.

And for the love of God, please stop the eye rubbing:

It might seem small, but avoiding excessive eye rubbing could help prevent Keratoconus from getting worse. I get it’s tempting especially when you have allergies or dry eyes.

Here is a video of me showing a better way:

Before you go, let’s look at the bigger picture

Keratoconus is just one example of how eye diseases can affect races differently, and how delays in diagnosis and treatment can lead to worse outcomes.

Addressing these disparities requires more research, better education, and improved access to advanced care.

It’s easier said than done, I know. But here are the steps you and I can take.

“Put your mask on first before assisting others.” Get yourself checked.

Pass it on. Now that you know about KC, tell someone else! Awareness is the first step toward action.

Join a clinical trial. If you have keratoconus, consider enrolling, not just for your own benefit, but to help improve treatment options for our community.

The more people of color in trials, the better we understand what solutions work best for us.

So, let’s spread the word.

If you or someone you know has blurry vision that isn’t improving with glasses, it might be worth checking if KC is the missing cone-nection.

Liked it? share it! 🖤

The content in this publication is intended for informational and advocacy purposes only. It is not formal medical advice. If you have concerns about your eye health or need medical guidance, please consult your healthcare professional.